5 Sept 2023

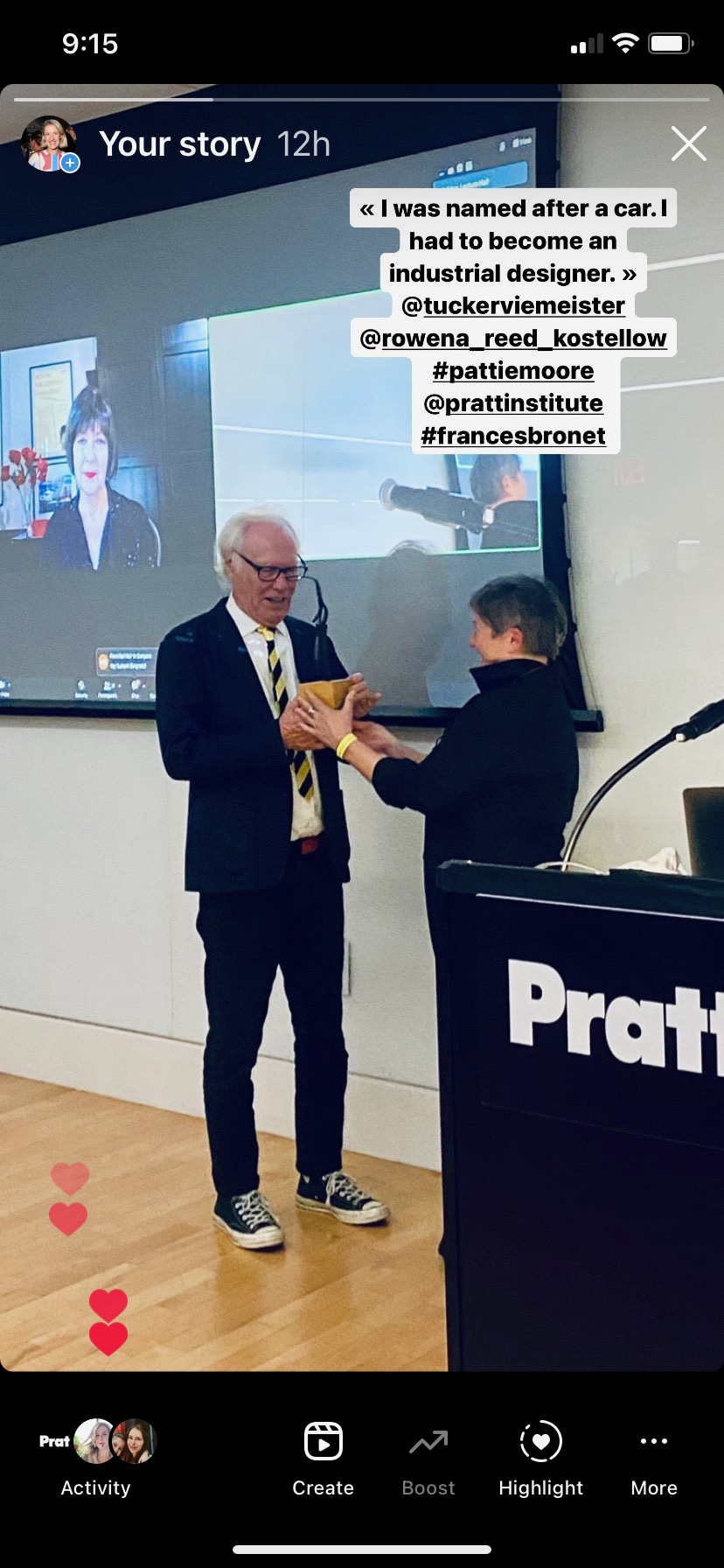

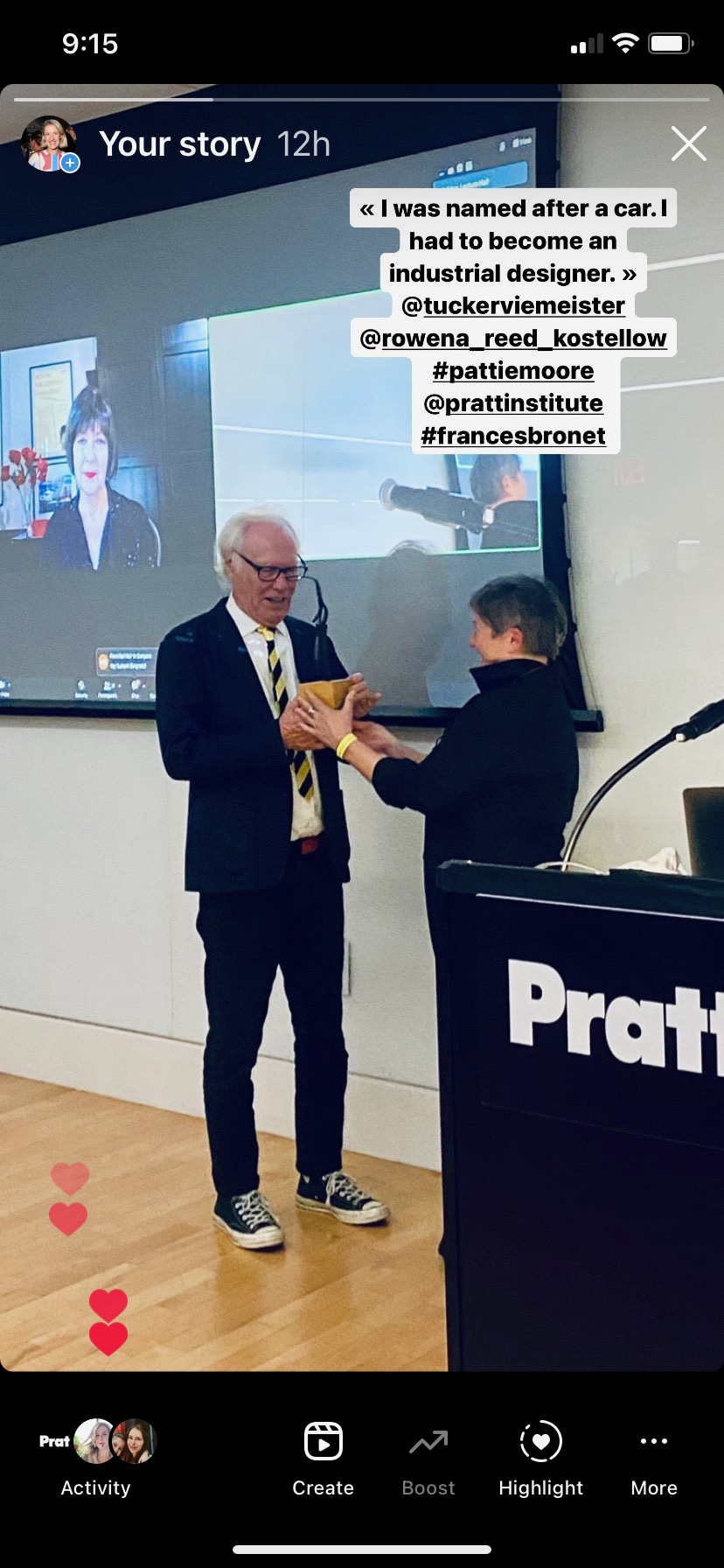

The Rowena Reed Kostellow Award honors Tucker Viemeister, BID ’74, its 2023 recipient

“Beautility,” is a word invented by this year’s awardee, Tucker Viemeister. His work embraces the concept that aesthetics are embodied in the design of human experience.

His father, Read Viemeister, was an early graduate of Pratt’s Industrial Design program. Thirty years later, Viemeister also graduated from the program, and in 2018, he was honored with Pratt’s Alumni Achievement Award. His designs are in the permanent collections of MoMA and the Smithsonian, and he holds 32 US utility patents. The press has described him as a “Wiz-kid,“ “Guru,” and “industrial demigod.” In 2016, the IDSA voted him one of the 50 “most notable” industrial designers.

Viemeister is most famous for creating the OXO GoodGrips with his partners at Smart Design in 1986. The famous handle design started as a vegetable peeler for people with arthritic hands. The form evolved from his simple question, “Why does design for older people always look frumpy?” This provocation was the starting point for his pioneering work in the Universal Design movement. Over his career, Viemeister’s designs range from voting machines (Microsoft) to exhibitions (Shanghai Planetarium) and contributions to the HyperloopTT project. He was EVP of Razorfish, opened frogdesign’s NY office, and founded “the LAB” at RockwellGroup. Viemeister’s latest product is for Loliware - a sustainably designed, single-use flatware made from seaweed, an earth-friendly material that dissolves after use.

Viemeister has been an outspoken ambassador for innovation+aesthetics in industrial design. A fellow of the IDSA, he just received the Lifetime Achievement Award. He is also the VP of the Architectural Society and is a prolific writer, lecturer and professor.

Attendees at the September 26th awards ceremony at the Pratt Manhattan Campus

(left to right) Karen Stone, Bruce Hannah, Tucker Viemeister, RitaSue Siegel, Linda Celentano, Louis Nelson

The ceremony was both in-person and virtual

7 Sept 2022

The Rowena Reed Kostellow Award honors its 2022 recipients, John Pai, BID ’62, and Keith Kirkland, MID ’15.

John Pai was Rowena’s student when he studied industrial design and then sculpture in the graduate program at Pratt in the 1960s. He became the youngest professor to be appointed to the faculty and lead Pratt’s fine arts and sculpture programs. Teaching for nearly four decades, Pai proved a talented educator, simultaneously nurturing generations of sculptors and fostering the burgeoning Korean artistic community in New York. Pai found success exhibiting his oftentimes unfolding, geometric sculptures at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. He is represented by Gallery Hyundai.

Keith Kirkland is deeply honored to have been considered for the Rowena Award which was given to 3 of his great teachers: Gina Caspi, Bruce Hannah and Charles Pollock. Reading about Rowena’s teachings in the book Elements of Design is what made him first choose to come to Pratt. He also studied at Keio University School of Media Design, Tokyo; Royal College of Art, London; FIT, NYC and Rutgers University in NJ. He was a TED fellow and MET MediaLab fellow. Combining design, technology, movement and touch his work with haptic navigation in a wrist-wearable Wayband helped the first blind person run the NYC marathon without sighted assistance.

John Pai on Rowena and Pratt:

“I was thinking about Rowena, my first impression of her was just as a human being. She told me one night that she needed some help repairing something in her house. She lived in Queens, and you know I lived in Brooklyn. She had a Volvo with a floor stick shift, and so she’s driving, in the midst of the Brooklyn/Queens traffic. As she’s doing this, she lets go of the steering wheel, and I said to myself, “Wow, this is not an ordinary woman!

“So, we started talking about one of her assignments or something. I think the sun came up when we started, and she kept talking. I swear, I think the sun went down, and she didn’t stop.

“You know, a lot of people had the impression that she was teaching some kind of methodology, because you hear the words dominant, subdominant, subordinate, and all that, and think it’s a formula for how to design. And, actually, when I saw her teaching, it was about something else; it was about dedication.

“And not only was she a fantastic teacher, but she was really concerned about the student learning. What did I learn from her? I thought, ‘I want to teach just like her.’

“People ask me when they see my early paintings, so you could have been a painter. What made you turn to sculpture? And it’s because whenever we had these long talks, we talked about everything; what we did last night…I happened to see the New York City Ballet for the first time, and I just loved everything about it, the form, the movement, the music, the choreography…and she could talk about all those things. And so, when you talk with somebody about so many subjects, you have to make five billion decisions or value judgments, and you’re developing your intuition in ways you can’t even calculate. But who’s willing to do that? How many teachers are willing to stay with one student and talk for hours?

“I remember we had some students who were not hearing the same things I was. They would listen to her talking about design. And she was talking about all the principles that you should be considering. And they thought they were dealing with some kind of design principle, like a formula you need to learn, and then you can talk about design. And, she said one day, ‘You know I’m not about formula. I’m about intuition. I want to develop your intuition.’

“One time we were talking about something, and I was kind of fidgeting about what I didn’t like about my own design. I couldn’t solve this problem, and I’m not happy with it. She slammed her pencil down and said, ‘Don’t, worry about your mistakes or weaknesses. Work on your strengths.’

“And it woke me up: ‘What are my strengths?’ That was a great lesson.”

“The 1960’s for Pratt, was a period of expansion and consolidation. Undergraduate sculpture existed mainly as a part of the Art Education Department, while a parallel program was offered in the Evening School. The Graduate School, under Calvin Albert, offered a complete MFA. In the process of sorting out graduate from undergraduate, I was asked to head the undergraduate sculpture program. In order to accommodate majors in Painting, Sculpture, Photography, and Printmaking, etc., the School of Art and Design was divided into Divisions: Art Division, Design Division, Foundation Division, Graduate Division, etc. I was asked to be the Director of the Division of Fine Arts, (Undergraduate.)

“I became a strong believer in the idea of developing intuition. It takes a lot of work, and you have to approach the problem in so many different ways, upside down, sideways, and cut it into pieces. I think there’s a side to art and design that’s basically very human, and it takes a kind of dedication. And I guess a kind of honesty, I used to have a drawing teacher who would say whatever about someone’s drawing, and then, “I don’t know what the hell I am doing! I am looking for the truth.’

“We were wondering, well, what is the truth? And he would say, ‘I’m looking for it.’

“Anyway, I thought we all had these teachers/characters who we remember. Bill Katavolos was one of those that a classmate — George Schmidt — and I got to know. One day Katavolos said, ‘You know Rowena? She’s a blue blood. And what does that mean? She’s royalty.’

“And it’s so great that we have heroes. And I’m so happy we can celebrate for her and for us.”